Jan 4, 2025

Differential Association Theory: Understanding Criminal Behavior

Introduction

When individuals surround themselves with the wrong crowd, it can lead to the development of questionable values and poor attitudes towards law and order. This socialization process is known as differential association. Edwin Sutherland, a prominent figure in criminology, dedicated his studies to understanding this theory, which outlines nine distinct precepts that explain how criminal behavior is learned. In this blog, we will explore these principles and their implications through the story of a young boy named Robbin.

9 Precepts of Differential Association

Differential association theory posits that criminal behavior is learned rather than inherent. Let's delve into how this theory unfolds through Robbin's experiences:

- Criminal Behavior is Learned: Robbin learns criminal behavior after meeting a new friend. This learning occurs through interaction and conversation, often supported by storytelling.

- Learning Occurs in Small Groups: The process primarily takes place in small, intimate groups. Unlike what some might think, mass media and video games have little impact on this learning.

- Sharing Insights and Techniques: The learning includes sharing insights, techniques, and attitudes that favor criminal actions. Robbin learns not just what to do, but also why it's acceptable in his social context.

- Motives are Learned: Robbin learns to classify laws as either good or bad. For him, laws protecting the property of the poor are good, while those protecting the rich are bad.

- Rationale for Criminal Behavior: An individual becomes delinquent when their rationale for breaking the law outweighs their rationale for respecting it. Robbin steals because he believes in taking from the rich to give to the poor.

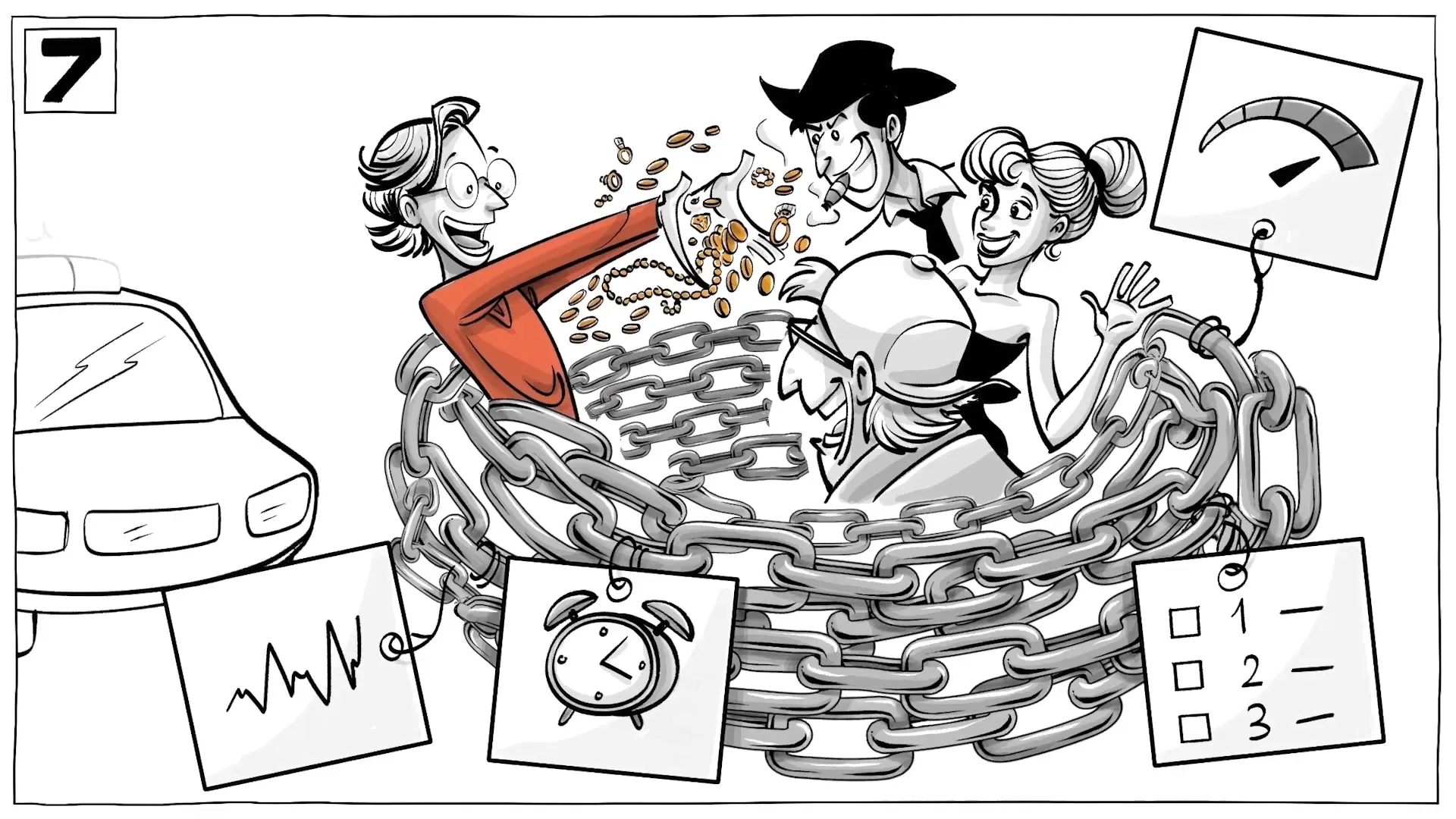

- Variability in Learning Experiences: Our learning experiences vary in frequency, duration, priority, and intensity. These factors all contribute to how criminal behavior is adopted.

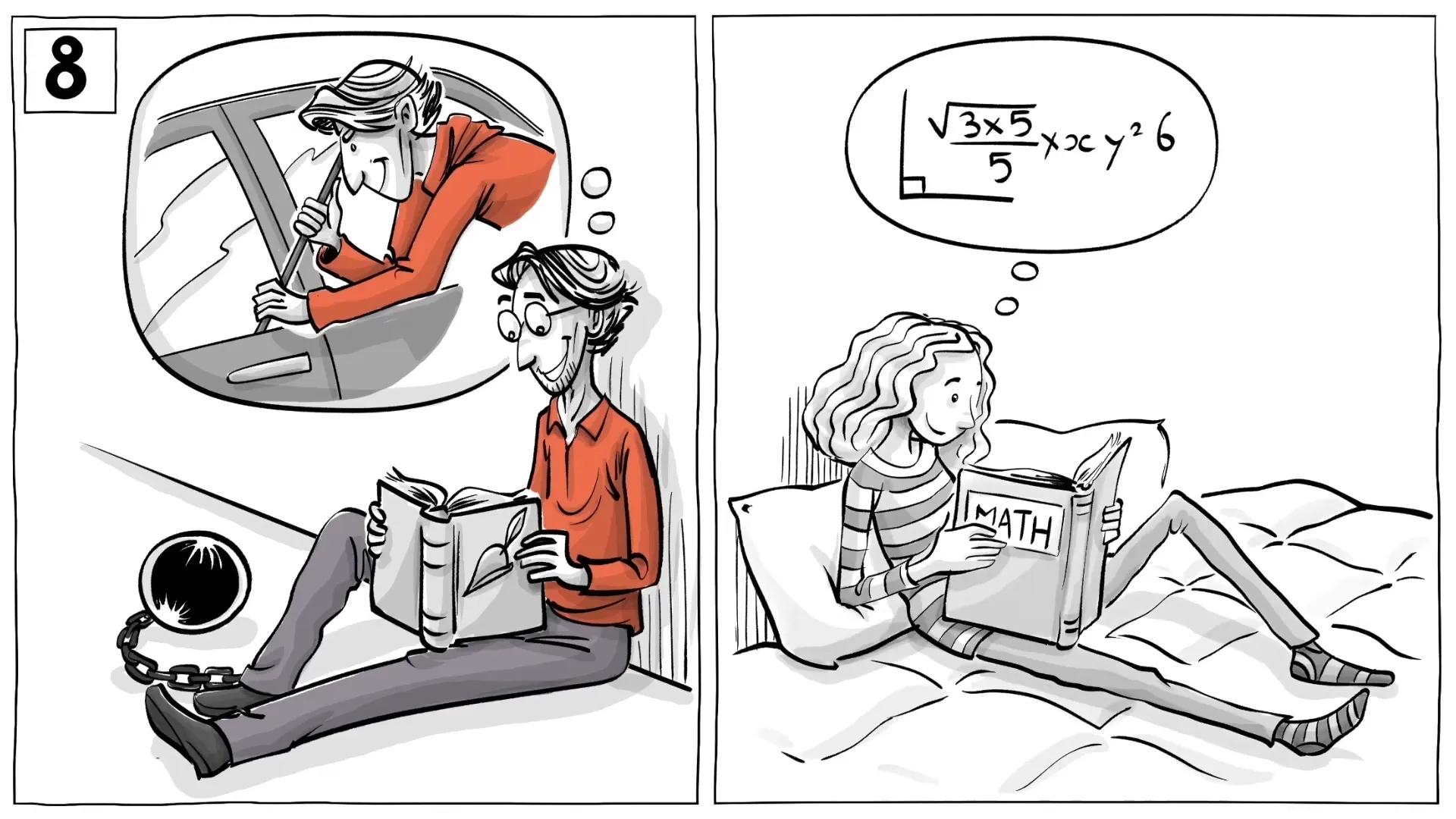

- Learning Mechanisms are Similar: Learning criminal behavior is akin to learning any other behavior. For example, Robbin learns criminality in the same way his sister learns math.

- Expression of Needs and Values: While criminal behavior can express one's needs and values, it does not explain them. Non-criminal behavior can arise from the same needs and values.

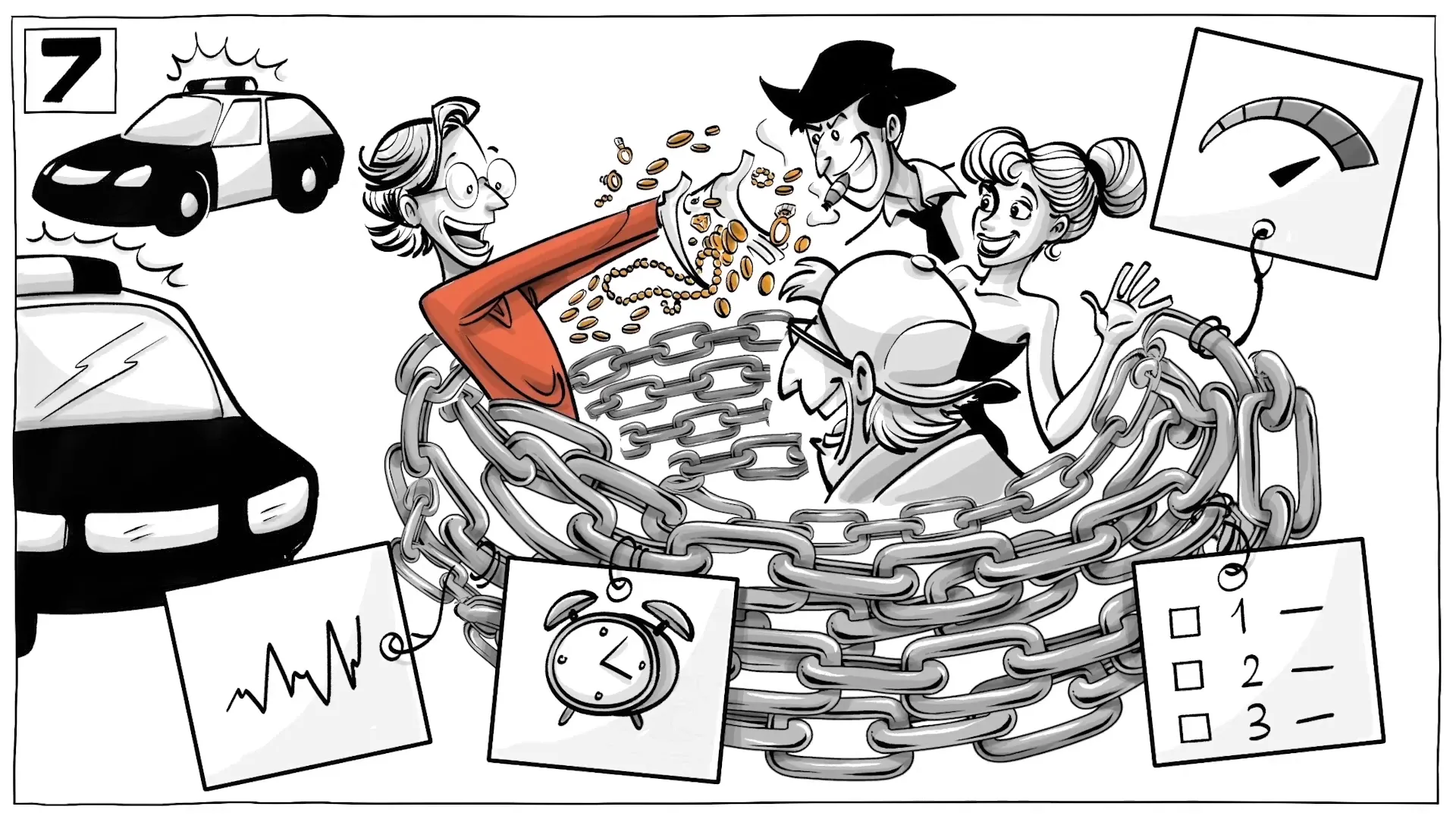

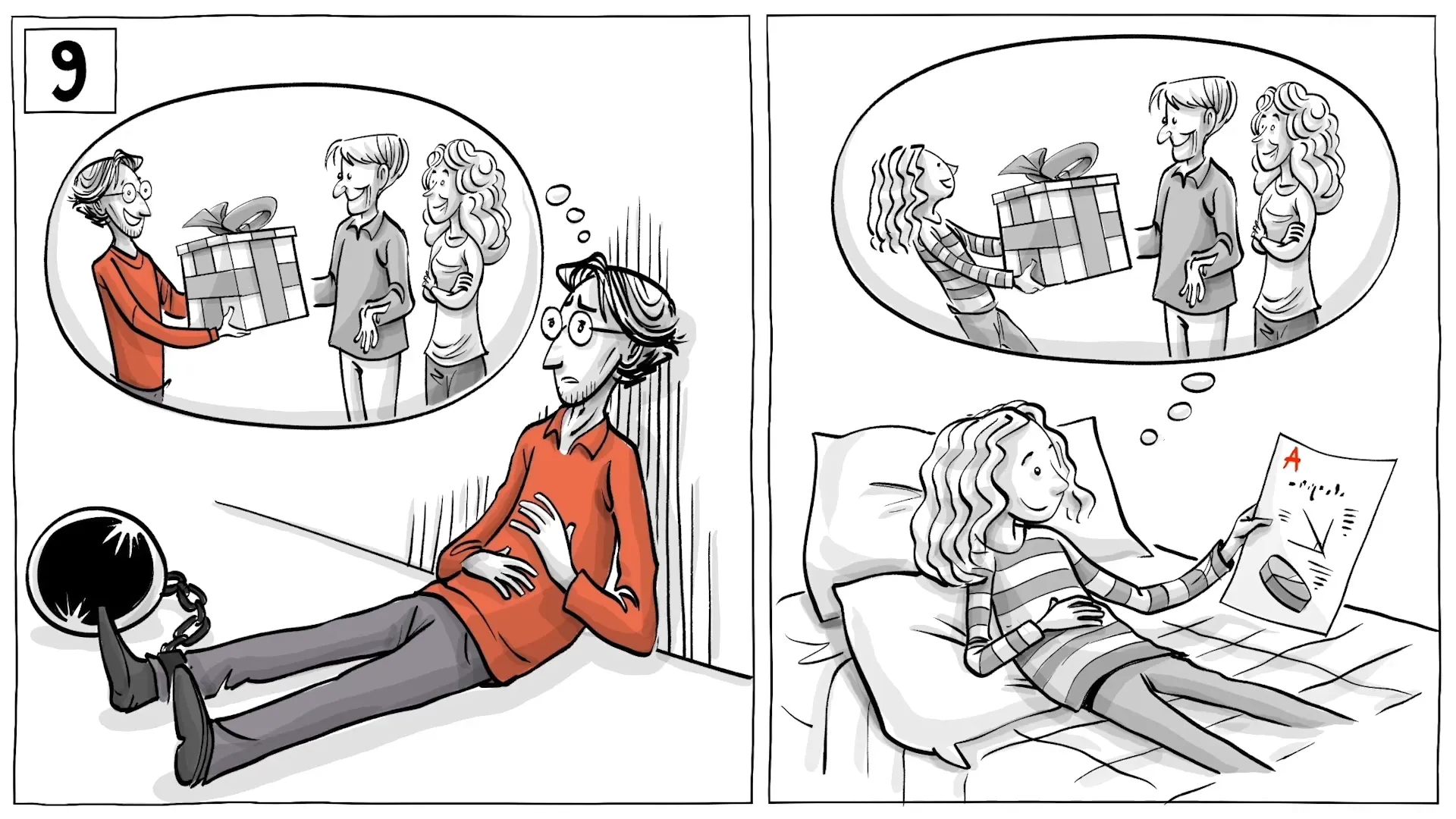

- Rehabilitation is Possible: Sutherland’s theory suggests that since criminal attitudes are socially learned, they can also be unlearned. This opens the door for rehabilitation, helping individuals like Robbin reintegrate into society.

What do you think?

Now that we've explored the principles of differential association theory, let's reflect on its implications. How can we keep society safe from crime, whether on the streets or in the corporate world? If Sutherland was correct, is jail truly the right place for young offenders? These questions prompt important discussions about crime prevention and rehabilitation strategies.

Conclusion

In summary, differential association theory provides a framework for understanding how criminal behavior is learned through social interactions. Through the story of Robbin, we see how individuals can adopt criminal values from their peers and how these behaviors can be unlearned. Sutherland’s insights into the social nature of criminal behavior highlight the potential for rehabilitation and the importance of addressing the social environments in which individuals are embedded.

This article was created from the video Differential Association Theory: The Psychology of Criminal Behavior with the help of AI. It was reviewed and edited by a human.