Jan 4, 2025

Cognitive Dissonance: Understanding Our Mental Conflicts

Introduction

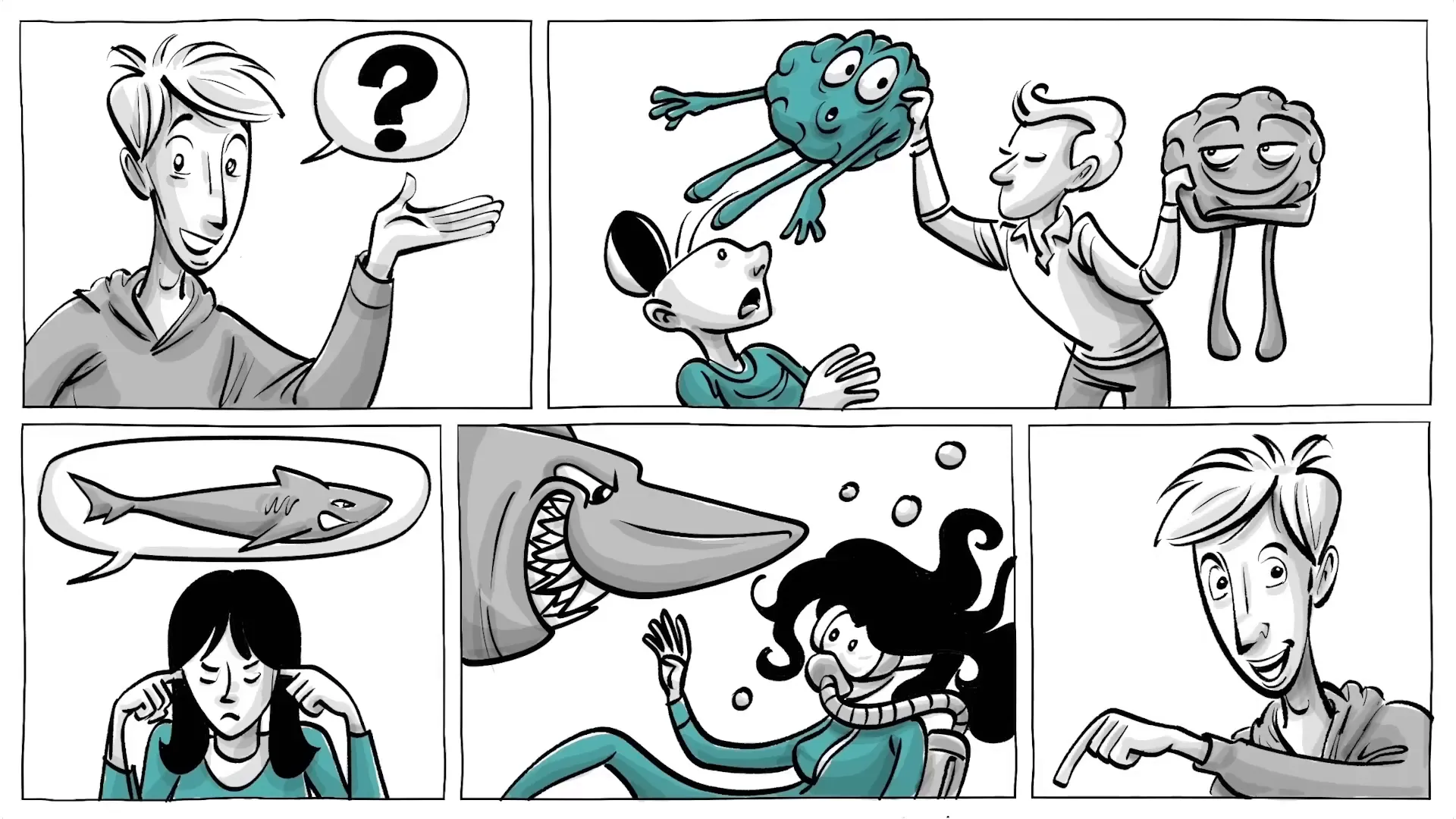

If you read a text or hear something new, your mind has a strong desire for order and consistency. The moment your brain holds two contradicting ideas, you experience distress. Your mind often resolves this problem by tweaking the ideas until they become consistent with the other stories you tell yourself to be true.

Meat eaters, for example, who are confronted with new information about how their dinner came about can either eat less meat, deploy strategies to cope with the new information, such as denial, or do a little bit of both. If two conflicting ideas are deeply ingrained in our identity, the mental imbalance can become overwhelming and intoxicate our thoughts — and as a result, we may believe even the most absurd conspiracy theories. To keep our sanity, it helps to learn about this phenomenon, known as cognitive dissonance.

The full story

After a severe earthquake in India, rumors circulated among people who felt the shock but sustained no damage about an even worse disaster that was supposed to strike. However, no disaster followed, and psychologists began to wonder why such rumors sprang into existence — it seemed counterintuitive that people would share and believe fear-provoking stories during such a difficult time. Nearly 20 years passed before Leon Festinger, a young psychologist, had a plausible theory: The rumors were not “fear-provoking” but instead "fear-justifying." The argument: if we feel afraid and safe at the same time, we invent explanations to reduce such conflicting states of mind. Festinger called this mental imbalance “cognitive dissonance.”

Cognitive dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is based on the idea that when two ideas are psychologically not consistent with each other, we change them and make them consistent. Festinger examined whether cognitive dissonance can be strong enough to believe in conspiracy theories even after they are proven wrong. To do so, two colleagues and Festinger joined a small apocalyptic cult led by Dorothy Martin, a suburban housewife. Martin claimed to receive messages from superior beings from another planet called 'Clarion'. The messages purportedly said that a flood would destroy the world on December 21, 1954.

The cult observation

The psychologists observed that many members quit their jobs and let go of their possessions in preparation for the end of the world. When the day came and passed peacefully, Martin claimed that the world had been spared because of the "force of good” that the members had spread. To cope with this situation and the heavy cognitive dissonance it produced, the psychologists hypothesized that the members had two options: they could either change their situations and let go of the beliefs and actions that formed the identity of their former self, or they could embrace new beliefs to stay in the cult and protect the image they have formed of themselves.

Festinger's assessment

And that’s exactly what happened. Some members faced the facts and left the cult to regain their sanity, while others believed Martin’s story to keep their threatened worldview alive. In their assessment, the psychologists concluded that three conditions made it especially hard for members to quit:

- If the members had deep convictions that were relevant to their everyday routines.

- If they had done things that were difficult to undo.

- If they received social support from other believers.

Leon Festinger later wrote, “A man with a conviction is a hard man to change. Tell him you disagree and he turns away. Show him facts and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point.”

What do you think?

What are your thoughts? Do you have an idea how we can change ours and other people's minds? If reason falls on deaf ears, can experience maybe do the trick? These questions linger as we navigate our own cognitive dissonances.

Conclusion

Cognitive dissonance is a powerful force in our lives, shaping how we respond to conflicting beliefs and experiences. Understanding this phenomenon can help us navigate our thoughts and decisions more effectively, allowing us to confront our contradictions with greater clarity.

This article was created from the video Cognitive Dissonance: Your Response to Conflicting Beliefs with the help of AI. It was reviewed and edited by a human.