Understanding the Robin Hood Myth and Its Implications

Introduction

Government programs are often portrayed as benefiting the poor at the expense of the rich. This narrative is commonly used to justify public welfare initiatives. However, economist Milton Friedman challenges this notion, labeling it the "Robin Hood myth." He argues that instead of aiding the impoverished, many welfare programs predominantly benefit the middle class, often at the expense of both the very poor and the very rich.

Robin Hood Myth

Friedman’s perspective reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of how welfare programs operate within our society. He posits that these programs are designed to benefit the middle class rather than the lower class. According to Friedman, the mechanics of political power and organization play a crucial role in this dynamic.

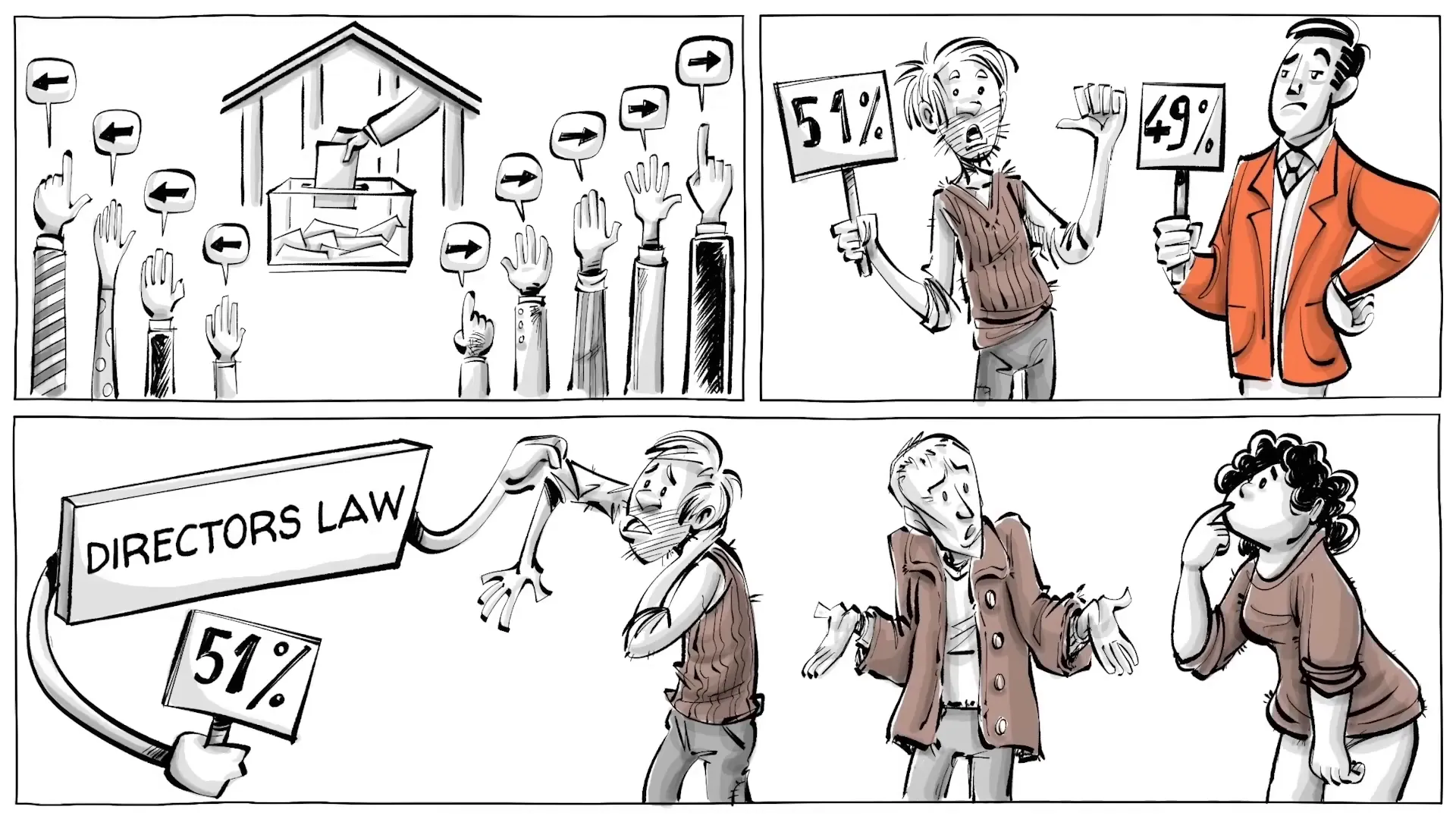

Under a democratic system, laws are typically passed by a simple majority—51% of voters. One might assume that the bottom 51% would enact laws that benefit them at the expense of the top 49%. However, this is not the case. The reality is that the lower-income individuals often lack the organization and political clout to advocate effectively for their interests, leading to a scenario where the middle class, who are more politically active, benefits the most.

Director's law

This phenomenon is encapsulated in what Friedman refers to as "Director's law." The law suggests that the bottom 51% of the population not only tends to be less fortunate but also is less likely to mobilize effectively for political action. In contrast, the top 51% are usually more comfortable with the status quo and less inclined to seek significant political changes.

The middle class, particularly those from the lower-middle to upper-middle class, are often the most effective political actors. They are generally more literate, have access to media, and often feel envy towards the wealthier classes, pushing them to seek out policies that cater to their interests instead of those of the poorest citizens.

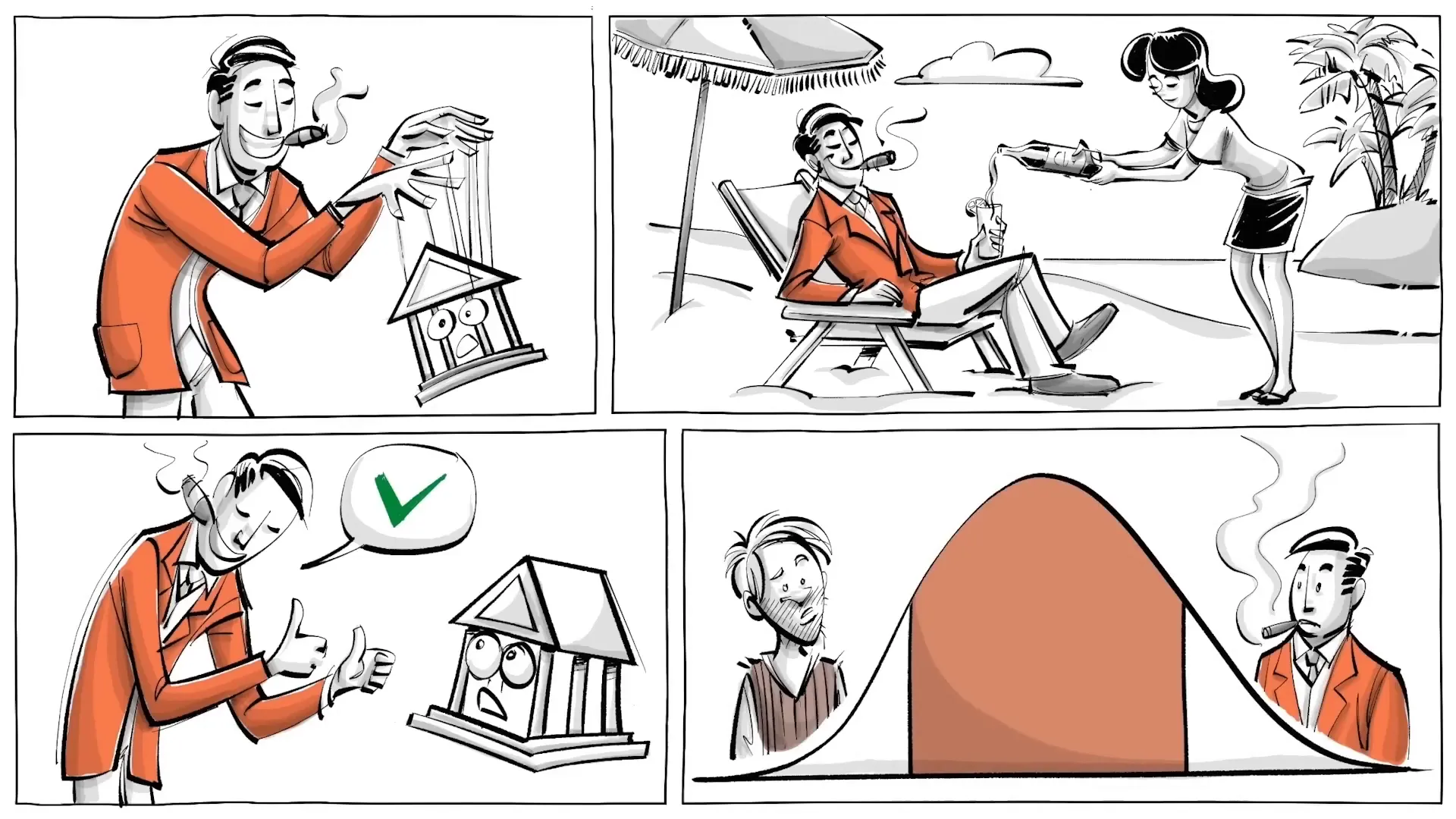

State-financed higher education facts

One of the most notable policies that exemplifies this issue is state-financed higher education. This initiative is often marketed as a means of providing equal educational opportunities for all. However, the reality is that the primary beneficiaries are typically individuals from middle and upper-class families.

While there may be occasional success stories of students from lower-income backgrounds, they represent a small fraction of the overall student population. Children from higher-income families tend to attend public universities for extended periods, allowing them to acquire skills and cultivate networks that facilitate access to better-paying jobs.

Taxpayers, including those from lower-income brackets, fund these educational programs, often for the benefit of families who are already well-off. As Friedman pointedly remarked, state-financed higher education essentially imposes a tax on individuals in lower-income areas, such as Watts, to subsidize the college education of children from affluent neighborhoods like Beverly Hills.

What do you think?

Friedman's analysis raises important questions about the effectiveness and equity of welfare programs. Was he correct in asserting that these programs disproportionately benefit the middle class? If so, what alternative solutions could be implemented to create genuine equal opportunities within a democratic framework?

These questions invite a broader discussion on how society can better address the needs of its most vulnerable members while ensuring that resources are allocated fairly and effectively.

Conclusion

Understanding the intricacies of welfare programs through the lens of Friedman's Robin Hood myth offers a critical perspective on how societal resources are distributed. It challenges us to rethink our approach to social welfare and consider more equitable solutions that truly benefit those in need, rather than perpetuating a system that favors the politically active middle class.